Introduction

Studying harder isn’t the same as studying smarter. Many students and lifelong learners spend hours re-reading notes or passively highlighting, believing time equals progress. The smarter approach focuses on strategy: setting clear objectives, using active techniques that force retrieval, designing a distraction-minimized environment, and measuring what actually improves recall and skills. This article gives you a compact, practical routine you can adopt one piece at a time. It’s grounded in widely accepted learning principles goal clarity, spaced practice, active recall, and feedback loops translating those theories into usable daily habits. Whether you’re prepping for exams, learning a language, or upskilling for work, these methods aim to help you learn efficiently while protecting your time and mental energy. Read on for four focused routines (each with a single, detailed paragraph) plus a short conclusion and FAQs to troubleshoot common study problems.

Plan with purpose

Start every study block by defining a concrete, measurable outcome rather than a vague time target. Instead of “study chemistry for two hours,” write “be able to explain the five steps of glycolysis and solve three related problems.” Break larger outcomes into 25–50 minute focused blocks with a single primary aim for each. Use a quick pre-session checklist: objective, resources needed, one retrieval task to perform at the end. This forces clarity and prevents wandering through materials with no endpoint. Prioritization matters tackle high-value topics (weak spots, upcoming exam content, or skill gaps) when your mental energy is highest. Reserve lower-value review or passive reading for low-focus periods. Track outcomes in a simple log: date, objective, whether you achieved it, and one note on what worked. Over time this data shows which objectives consistently need more time and where your planning needs to change. Planning with purpose turns study hours into measurable learning progress.

Use active learning techniques that actually stick

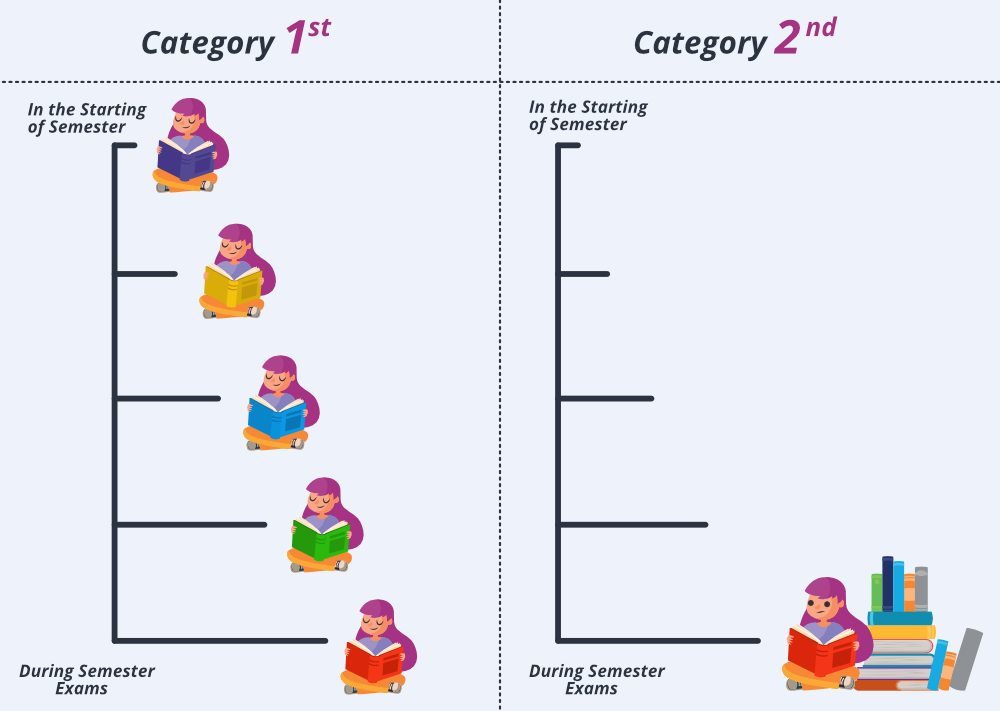

Passive review rarely produces durable learning; active engagement does. Center your study sessions on retrieval practice self-testing without referring to notes because forcing recall strengthens memory traces far more than re-reading. Combine this with spaced repetition: revisit difficult topics on an expanding schedule (for example, 1 day, 3 days, 7 days) to combat forgetting. Mix in interleaving: instead of studying one type of problem repeatedly, alternate related but distinct problems to deepen discrimination and transfer. Explain concepts aloud as if teaching someone else (the Feynman approach), and create quick one-page cheat sheets that summarize key ideas from memory. When working problems, always attempt to solve from scratch before consulting worked examples; afterward, annotate the solution with your own concise rationale. These active strategies take more mental effort, but that effort is precisely what converts short-term reading into long-term knowledge and skill.

Optimize your environment and time for focus

Design your study environment to minimize decision fatigue and interruptions. Remove obvious distractions: silence notifications, use website blockers during deep blocks, and keep only the materials you need on the desk. Light, posture, and short movement breaks matter work in natural light when possible, use an ergonomic chair, and stand or stretch briefly between blocks to reset attention. Use time-anchored routines like the Pomodoro method adapted to you (e.g., 50 minutes work, 10 minutes break) and schedule high-cognitive tasks when you’re naturally alert many people do best in morning hours, others in late afternoon. Batch administrative tasks (email, scheduling) into a single short slot so they don’t fragment study flow. Finally, create contextual cues: a single “study playlist” or a special notebook that signals to your brain this is learning time. Environment and time optimization reduce wasted effort and make deep work more likely and more productive.

Track, review, and iterate

Good study routines are experiments that require data. After each study block, spend two minutes rating how well you met the objective and noting what errors or confusions came up. Weekly, review your log to spot patterns: which topics need more spaced repetition, which types of practice sessions yield faster gains, and which environmental factors help or hurt focus. Use small formative checks quizzes or practice problems to gauge real retention, not just perceived familiarity. When a technique stops working, change one variable at a time (session length, order of topics, or study environment) so you can identify the causal factor. Celebrate small wins consistently achieving objectives and convert them into scaffolding for tougher goals. Making feedback systematic prevents plateauing and keeps your routine adaptive; learning becomes a process of continuous refinement rather than rote repetition.

Conclusion

Smarter study routines aren’t complicated; they’re intentional. By planning precise outcomes, favoring active learning, optimizing your surroundings and schedule, and treating study as an iterative experiment, you transform time spent into lasting knowledge. Start small: pick one change (clear objectives, retrieval practice, environment control, or feedback tracking) and apply it consistently for two weeks. You’ll quickly see where to expand and which habits deserve permanence. Over time these small, evidence-informed shifts compound into more efficient learning, less stress before deadlines, and better retention when it matters most.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: How long should a single study block be?

A: It depends on individual focus spans commonly 25–50 minutes for deep work. Use longer blocks (50–90 minutes) for complex problem-solving if you can maintain focus, and shorter blocks with more frequent breaks if you struggle with attention.

Q: Is highlighting useful?

A: Highlighting alone is low-impact. If you highlight, convert highlighted sections into active tasks: summarize from memory, create retrieval questions, or explain the idea in your own words.

Q: How do I stop procrastinating?

A: Break tasks into tiny, clear objectives and start with a 5-minute commitment. Use an accountability partner or schedule the task into a fixed calendar slot to reduce initiation friction.

Q: Can I apply this routine to group study?

A: Yes define shared objectives, assign active tasks (e.g., each person explains a concept), and use group quizzes to create retrieval practice and peer feedback.

Leave a Reply